Bread and Roses: A model for downtown

All,

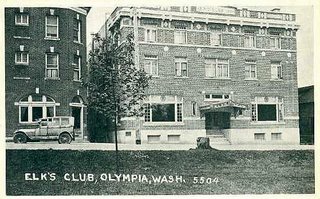

Olympia, WA

Olympia has her own way. You can not always pin her down. In the end she will be like nothing else and she will always struggle to be only who she is.

In their November 6th issue, editors of The Olympian proclaimed that Lacey was a “role model for its neighbors” because of the city’s rapid growth in retail sales through “enticing business patrons.” In particular, the editorial compared Lacey’s economic growth to that of Olympia’s – where retails sales dropped. The reason for Lacey’s increase in sales growth was its business friendly environment, while one of the reasons for Olympia sales decline was its “crisis of public safety” (as one Olympian put it before the city council) in its downtown. Before everyone else follows the lead of editorial board of The Olympian, and jumps on the “Lacey model” for economic growth, it is important to asks some important questions: Is The Olympian’s analysis of the situation accurate? Specifically, is there really a “public safety crisis” in downtown, and is Lacey’s formula for economic growth sustainable?

First: the public safety question. Despite all the rhetoric about the dangers of Olympia, comparatively speaking Olympia has a very low violent crime rate. According to FBI figures for 2004, Olympia experienced 333 violent crimes per every 100,000 persons. This is low for both state and national figures. For Washington State the average is 461 violent crimes per every 100,000 persons, and for the nation it is 596 per every 100,000 persons. The figures become even more interesting when Olympia is compared to its neighbor Lacey for the past few years. In 2003, Olympia had a higher rate of violent crime than Lacey. (Olympia was at 3.3% while Lacey was at 2.8%). But, a shift occurred in the following years. Olympia had 145 acts of violent crime in 2003, by 2005 that figure had dropped to 115 violent crimes. While Lacey’s violent crime rate jumped in 2004 (to 3.3%), and in 2005 remained higher than Olympia’s. Olympia had 258 violent crimes per every 100,000 persons, while Lacey had 272 violent crimes per every 100,000 persons. What this means is that for that last few years violent crimes has been going down in Olympia, which is counter to national trends, while Lacey’s rate has moved up.

This evidence makes clear that the so-called “public safety crisis” is a delusion. Its remains alive and is seriously debated only because of an intense class-bias against the poor and homeless. People with this bias automatically assume that if the homeless or street vagabonds are hanging out together then they must be “up to no good,” or if a person is engaging in anti-social behavior in the downtown, then that person must be homeless. A perfect example of this is the complaint of public urination in the downtown. Often times the discussion makes references to Olympia’s homeless with the assumption being that they are the ones doing the act. However, the Olympia Police Department has acknowledged that the majority of cases of public urination in the downtown involve late night bar patrons who don’t tend to be homeless.

Second: the economic question. The editorial in The Olympian attributes Lacey’s recent economic success to it ability to attract major corporate enterprises such as Home Depot and Costco with its “business-friendly environment.” In this, the editors for The Olympian are accurate, but also a bit misleading. First off, it is unfair to economically compare Olympia and Lacey in the manner that was done in the editorial and it construes important economic truism. Lacey is a very young city – especially compared to Olympia. It has only been incorporated since 1966, and that’s important but it means that Olympia and Lacey have two very different economic infrastructures. Lacey is very underdeveloped compared to Olympia. Rapid economic growth through corporate enterprises is possible in underdeveloped areas because you are starting from nothing. Olympia on the other hand has built itself off of industries and businesses that have survived for decades. Allowing major corporate enterprises to move could seriously disrupt these foundations – which, for Olympia, would be locally owned businesses that are mostly located in the downtown core.

There is also the issue of how large corporation enterprises tend to depress the economies they enter over time. An essential part of any development plan is the ability to build off of previous gains. This is difficult to do in a corporate friendly atmosphere. Dollars spent at Home Depot and Costco vanish from circulation in the local economy. The ability of corporations to under-cut prices and offer more services ends-up destroying small independent businesses. The low pay and lack of job security for people who work at these business stagnates the economy because they only make enough money to cover their basic necessities - not to mention the hardship and cruelty of poverty itself. In the end, this corporate friendly environment is not sustainable; it leads to economic growth, but not necessarily to economic development.

Perhaps the biggest and most important lost in this corporate friendly environment is that of civic virtue. The re-organizing of city life - with the elimination of public spaces, the arts, and recreation, essentially transforming the city into one big mall – also change its people. Soon, people start identifying more as consumers, managers, and workers, than as citizens. Civic participation and social life ends-up taking a back seat to corporate controlled markets. People become more concerned with shopping than they do with voting - and even less so with political organizing. Ironically, this atmosphere of isolation and rabid materialism become a breeding ground for the anti-social behavior that the editors of The Olympian claim is preventing people from shopping in downtown Olympia.

The editors were right that Lacey’s neighbors do have a lot to learn from the city, but it’s what not to do. This of course doesn’t mean that Olympia is “good” and Lacey is “bad.” Both of the cities have their problems, and both have people who are working for greater democracy inside of them. What this does mean is that if either city is to move forward in a manner that supports all its citizens then it must craft policies with a focus on social and economic justice. If not, then “lost sales” will be the less of either city’s hardships in their (maybe not so distant) futures.